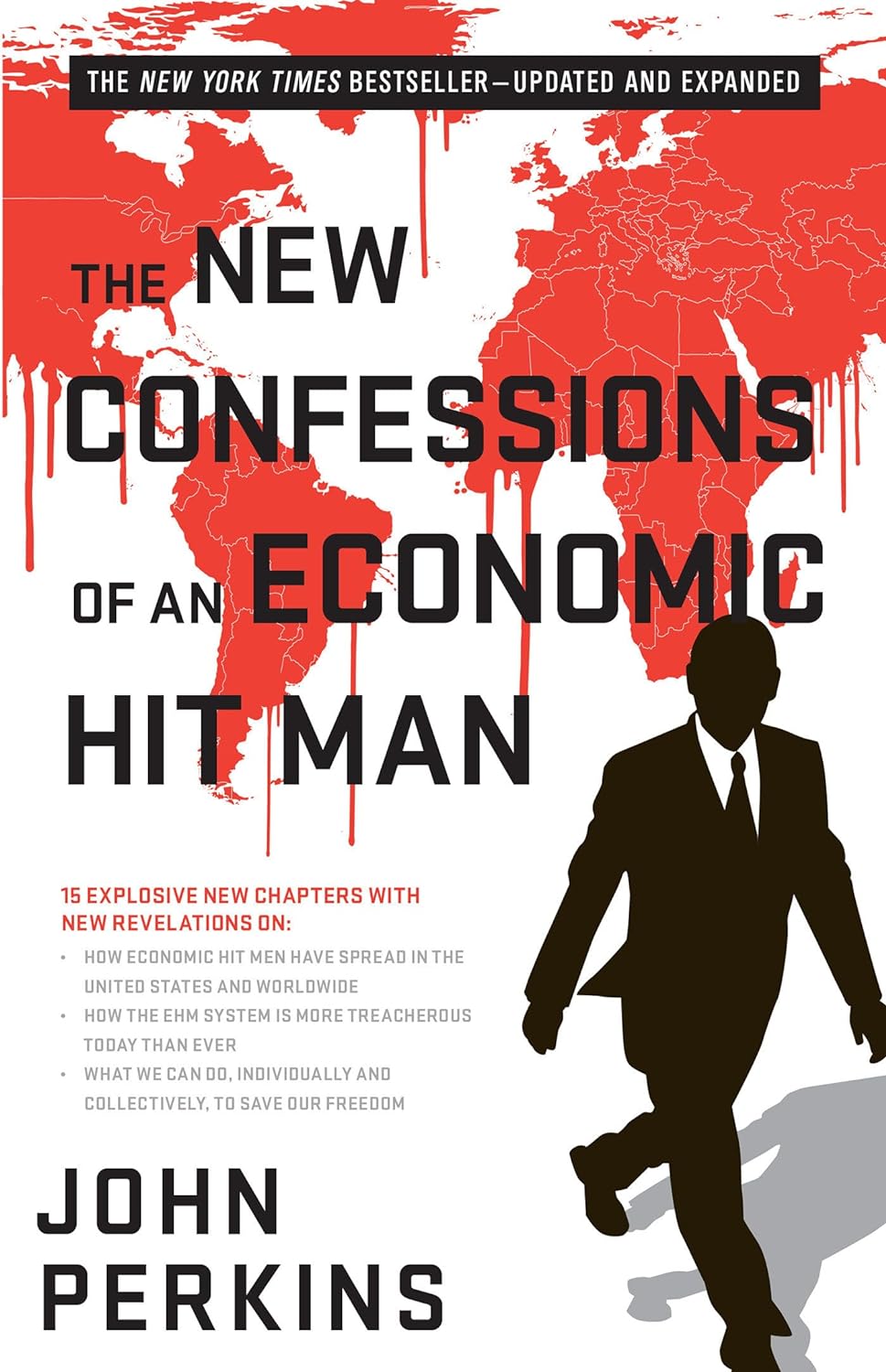

The Art of the Hit

WorldView speaks with author and RPCV John Perkins about the latest edition of his bestselling book Confessions of an Economic Hit Man

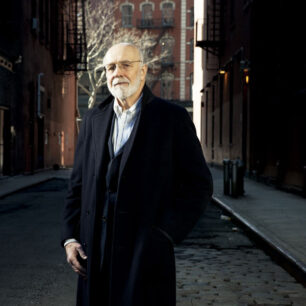

John Perkins is a New York Times bestselling author, international speaker, and activist.

As Chief Economist at a major international consulting firm, Perkins advised the World Bank, United Nations, IMF, U.S. Treasury Department, Fortune 500 corporations, and countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. He worked directly with heads of state and CEOs of major companies.

John’s classic, Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (2004) spent 73 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and has been published in more than 35 languages. It was a groundbreaking exposé of the clandestine operations that created the current global crises. The New Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (2016) brought the story of economic hit men and jackal assassins up to date and chillingly home to the U.S. It went on to provide practical strategies for each of us to transform what he calls the failing global death economy into a regenerative life economy. The two books have sold more than 1.9 million copies. The third version of the book takes a look at China’s economic hit man (EHM) strategy, exposes corruption on an international scale, and offers much-needed solutions for a more just and equitable world economy

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

How did your Peace Corps experience impact your career and motivation to write Confessions?

My experience was primarily in the Amazon rainforest, and I extended a year in the high Andes, working with Indigenous people. Before my assignment, Peace Corps sent me to eight weeks of training in Escondido, California, to learn Spanish and how to form credit savings co-ops, since I’d graduated from business school. Then they sent me to Quechua territory to work with people who didn’t speak Spanish and had no currency whatsoever.

I very quickly learned that I had nothing to offer these people, but they had a great deal to teach me. That’s such an important element of the Peace Corps, and I think what John Kennedy and Sargent Shriver had in mind. I wish every young American had the opportunity to do something like that.

Later, when I became chief economist at a major international consulting firm and ended up having between 30 and 50 people working for me at various times, I would always prefer, if I could, to hire Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, because I knew if they’d survived two years in the Peace Corps, they could handle working internationally in another culture. So for me, the Peace Corps experience was extremely valuable.

When did you go from thinking of yourself as a well-intentioned global consultant to an economic hit man?

I had the [chief economist] job for 10 years, and for most of those years I thought I was doing the right thing. The World Bank certainly advocates the message that if you want to help a poor country, you invest huge amounts of money in infrastructure, like electric power systems, highways, ports, and airports—and statistically, you can show that when you do that, the economy grows the GDP. So when I went in as a consultant, I [believed] I was going to do really good work. I was going to help these countries. I was going to continue what I started in the Peace Corps.

But over time I began to see that GDP measures how well the rich are doing, mostly through the success of large corporations. GDP is not a measure of overall prosperity in most countries. It took me seven years to really understand that what I was doing was helping the rich and helping corporations, but I wasn’t helping the majority of people in these countries. I’m flying first class around the world, staying in the best hotels, eating at the finest restaurants—the opposite of the Peace Corps experience. I was in denial for a few years, trying to convince myself—and the whole system was trying to convince me too—that what I was doing was good. But it was bothering my conscience. I’m not trying to say that all foreign aid is bad, but a huge amount of it is used to help the rich get richer and the powerful more powerful.

What’s the origin story behind the title? It’s so catchy.

Sometimes, when I’d get together with other guys that had jobs like mine, we’d be sitting around a bar in a place like Bogotá or Jakarta having a few drinks, and [someone would] say something like, “Well, I gotta get up tomorrow morning and go out and hit the Ministry of Finance.” “Hit” the ministry. Like the economic version of a mob hit or something. It was sort of a tongue-in-cheek thing. It’s a little bit like [how] CIA agents might act in private. They don’t call themselves “spies” or “spooks” in public, but when they sit around and have a few glasses of wine they might say, “God, I gotta go out and do some spook work tomorrow.” When I started writing the book, it seemed like a good title to use.

Doesn’t global investment and economic development help serve the U.S. national interest, though?

I think it’s not about helping U.S. national interests, because [foreign aid] often destabilizes these places, which is, quite frankly, bad for most people in the United States. It’s good for a few people: those who own the big corporations, or the people who are heavily invested in Lockheed Martin or other big defense industries. If you look at places like Afghanistan or Iraq, they made a lot of money. And you could say the same thing about lots of parts of the world right now. The companies that benefit from destabilized countries are not just the ones like Lockheed Martin—it’s also Microsoft and Google and companies like that. The war economy is such an important part of our economic system, but it doesn’t help most Americans, although we may not realize that. We may think we’re doing the right thing in many of these cases.

But the fact of the matter is, our tax money is being spent to kill people and destroy economies. And then you get the opportunity, once you destroy an economy, to rebuild it.

Like what Naomi Klein wrote about in The Shock Doctrine

Yes, exactly. And that’s what I call “the death economy.” To a large degree it is an economy based on death, on warfare or the threat of warfare. Eisenhower defined it as the military-industrial complex. It’s also about polluting and consuming to the point of self-destruction.

Do you want to expand on the domestic component of that?

So there have been three waves of what I define as an economic “hit.” The first is sort of generic. Those of us who were basically trying to bring resources and profits home to U.S. industries, we worked primarily for the World Bank, or the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the IMF, the Treasury Department.

Then a second wave evolved, which was the big international corporations, and all of them have their own version of an economic hit man. They go to developing countries to build a new manufacturing plant—and we’re looking at you, the Philippines, but we’re also looking at Indonesia and Malaysia and China—and we’re going to go wherever we get the best deals, wherever we pay the least taxes and the lowest wage rates to get good workers. Every major international corporation has lobbyists promoting this approach on some level. Sometimes they call themselves consultants.

And the third wave is China. I was once invited to teach at an MBA program in Shanghai to mostly Chinese students who had been singled out to be the future leaders of the economy. I very quickly realized that I was there to help them understand how to be better economic hit people. The Chinese were much more effective [at it] than we were. They’ve learned this model that we developed in the United States and taken it to another level. Now they’re the number one investor and trading partner with many more countries than the United States is.

How do “economic hit” methodologies differ in the Chinese model from the American one?

The first way is fear. When we introduce fear—that countries must be fearful of [their] neighbors, communism, the United States, or whatever. This also includes anxiety over insufficiency. Like, “OK, you poor country, you have major insufficiencies and we’re gonna help you out of that.”

Number two is the debt element. China’s approach to debt is quite different from ours when it comes to setting conditions on aid or investment. The World Bank almost always attaches conditionalities around what kind of political system a country must have first, as well as privatization of the economy, etc. The Chinese make a point not to do that.

Perhaps the most significant one is the last one, which is divide and conquer. And that’s been a keystone of exploitation, of imperialism, for thousands of years. You help a country and then set it against its neighbors to help you win its neighbors over to you: “We’ll give you a ‘most favored nation’ clause.” A country may have great trading agreements with the United States. China goes in and says, “We’re going to help you build ports, big deep-water ports, and help you have trading relations with Africa, with Asia.” The truth is, the Chinese brought some 800 million people out of poverty and [achieved] economic growth of around 10 percent a year for 30 years. No one else has ever done that. So if you’re the leader of a country in Africa or Latin America or other parts of the world, you may say, “Yeah, well, we don’t want to necessarily replicate the Chinese government, but we can still use their economic system.”

The other thing is that, since the early 1970s, there’s been no increase in the real average wage in the United States. Then there’s inflation. And of course I keep hearing, in Latin America and elsewhere, real criticism of the U.S. political model: “If the United States is a democracy, we don’t want it. You’re dysfunctional. You can’t even agree on a budget for more than three or four months at a time. You can’t agree on anything.”

So many Peace Corps Volunteers come back and want to write about their experience or things they’ve done that were inspired by their experience. Do you have any guidance for young writers who are looking to get published?

Confessions was rejected by 39 publishers. My advice would be to stay persistent. I love to write; it’s my greatest love. If you love to write, just write.

You know, any Peace Corps Volunteer that’s had experiences overseas, there’s something to share there. I think we should feel blessed to be alive at this time of terrible crisis, because there are incredible opportunities and challenges for changing the way we see ourselves as human beings on this planet.

I think Returned Peace Corps Volunteers are in an especially good position to enlighten people [about] aspects of the world that most Americans are not aware of. And if no publisher buys your stuff, self-publish it. And then maybe if it’s good and you want a publisher, they’ll do it. The other aspect of self-publishing is, you know, your royalties are a lot higher!

Watch a Ted Talk by John Perkins:

Robert Nolan (Zimbabwe 1997-99) is editor in chief of WorldView

Related Articles

Made in America

Charlie Clifford (Peru 1967–69) is the founder of Tumi Inc., a global travel luggage brand, as well as Roam Luggage.…

“Bigger Than Peace Corps”

California Service Corps is the largest state-based service program in the U.S. , with more than 10,000 volunteers across the…

Signal Boost

The digital world is awash in voices seeking monetary reward or improved social status, as the online acronym goes, IRL…

Garden of Refuge

As part of our commitment to continued service, the Seattle Peace Corps Association (SEAPAX) is partnering with World Relief Western…