The Domestic Dividend: Part II

How Peace Corps makes America stronger

It was more than altruism that motivated John F. Kennedy to start Peace Corps. By 1961, the Cold War had split the world into opposing camps: the communist East and capitalist West. On a late-night campaign stop in 1960, Kennedy informed a large group of University of Michigan students that the Soviet Union “had hundreds of men and women, scientists, physicists, teachers, engineers, doctors, and nurses . . . prepared to spend their lives abroad in the service of world communism.” In the spirit of Cold War competition, he challenged those young Americans into do the same—to give a few years of their lives to serve their country. At the time, the United States had no non-military program for which citizens could volunteer—hence Peace Corps. Kennedy envisioned it as benefiting not only developing countries by providing much-needed skilled labor, but also the United States, by spreading the American brand abroad in a spirit of goodwill and friendship.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye coined the term “soft power,” but Peace Corps fit Nye’s description: a foreign policy tool that achieves desired outcomes through attraction rather than coercion. Traditional instruments of power, such as military force and money, could go only so far. Kennedy, a Navy vet himself, knew that wars were not won with bombs alone; he believed that idealistic Americans working at the local level could help win the war of “hearts and minds.”

Since 1961, more than 240,000 Peace Corps Volunteers have served in 62 countries, forming a powerful global network that benefits both the host countries and the United States. In 2024 alone, Peace Corps Volunteers taught subjects such as English, math, and science to more than 212,000 students; advised 24,000 farmers on food security; planted 55,000 trees; provided HIV services to 78,000 individuals, and provided entrepreneurship training to more than 6,500 people. Volunteers have not only helped the communities they serve, but have also enhanced America’s image abroad. All that costs each American taxpayer $1.26 annually, on average—about the price of a quarter of a cup of coffee from Starbucks.

An Agency That’s Able to Adapt

Through the years, Peace Corps has been able to innovate and deploy resources strategically. In 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, Peace Corps responded with programs to help the Eastern Bloc countries transition to democracy and build small businesses. Then, two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed, officially ending the Cold War. To support the newly independent countries, the United States sent foreign aid packages that included not only military assistance and money, but also Peace Corps Volunteers: an example of hard power and soft power working in tandem.

To adapt to these new realities, the shape of Peace Corps service has morphed over time. The traditional 27-month stint is still available, but there are other ways to serve, including virtual opportunities. Peace Corps Response, originally called Crisis Corps, places skilled professionals in short-term, high-impact projects that can last from three to months. Hundreds of returned volunteers have signed up for second tours and served in countries ranging from Bosnia to Guinea to El Salvador to help communities recover from conflicts, hurricanes, earthquakes, and more. Undoubtedly, the U.S. has core interests at stake in these countries, from curbing migration to combatting Islamic extremism. It’s hard to see how the presence of Peace Corps Volunteers on the ground doesn’t help project American strength and commitment.

A “unique cohort” of Americans

Government officials, including presidents, have described how the trajectories of their lives were changed as a result of their contact with PCVs. Uganda’s Chief Justice Burt Katureebe, for example, came from a family of goat farmers and says he would have followed in the family tradition had he not landed in the classroom of a Peace Corps teacher. Ambassador Mark A. Green recalled an exchange with a Tanzanian official while presenting his diplomatic credentials to the country’s president when a “protocol officer proudly took me aside and related how he had once been taught by a Peace Corps Volunteer.”

Not surprisingly, many RPCVs wind up in government service. The Peace Corps has been an excellent training ground for the Foreign Service. There are 20 RPCVs in the current incoming class of FSOs, and hundreds more serving as diplomats at every level, including more than 65 RPCVs who have served as ambassadors. Kathleen Stephens (PCV South Korea 1975-77) held diplomatic posts in China, the U.K., and Portugal before becoming ambassador to South Korea. Of her Peace Corps service, Stephens has said “this is where I learned the qualities I needed to be a diplomat; I learned how to endure hardships and convince others.”

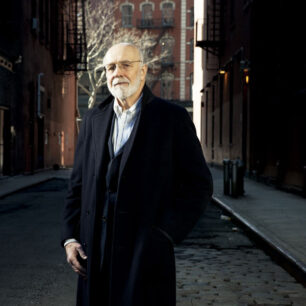

The 250,000 Americans who have served in the Peace Corps have been America’s most important representatives and ambassadors of goodwill around the world, promoting who we are and what we want everyone to be able to achieve. – Amb. Johnnie Carson

Johnnie Carson (Tanzania 1965–68), a retired U.S. ambassador whose career included three ambassadorial posts in Africa, said of Peace Corps that it is “the singular, best international voluntary organization ever created. Since its inception, it has allowed the United States to project its most important values in every part of the world. The 250,000 Americans who have served in the Peace Corps have been America’s most important representatives and ambassadors of goodwill around the world, promoting who we are and what we want everyone to be able to achieve.” After serving in small villages or large towns overseas, he continued, Volunteers “bring back that expertise and knowledge to the United States, to their families, churches, cities, and communities.”

Soft Power Requires Staying Power

“Bringing the world back home,” the agency’s third goal, is perhaps its most underrated one. “We don’t fully appreciate that domestic dividend that the Peace Corps provides to the United States,” said former Peace Corps Director Mark Gearan, now president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Living and working overseas gives RPCVs a deep cross-cultural understanding, practical language skills, and a nuanced appreciation of global issues. “It’s a unique cohort of Americans,” Gearan said.

Like so many RPCVs, I developed a lifelong connection to and fascination with my country of service. In 2001, six years after my Peace Corps tour ended, I returned to Uzbekistan on a journalism fellowship. I was traveling among the villages in the Fergana Valley in Central Asia. The territory has long been in dispute among competing superpowers: The 19th-century imperial struggle for control of the region was known as “The Great Game,” with Britain and Russia trying to best each other in the race for an overland passage to India. Russia, under the czars, ultimately took control of the region, but it wasn’t until the Bolsheviks took power in the 1920s that the country made a concerted effort to influence Uzbek culture. Modernization efforts—including electricity, running water, and mandatory education—brought improvements to people’s standard of living that went a long way toward establishing Soviet power in the region.

During my trip, an Uzbek man referred to an electric light as “Lenin’s lamp.” The phrase stopped me cold. It was like seeing a message etched on an ancient tree and surrounded by a heart: The U.S.S.R. was here. The things that matter to people are those that improve their daily lives. Peace Corps has left many lamps behind in the global world. The more we keep lit, the stronger America will be.

Beatrice Hogan (Uzbekistan, 1992–1994) is on the editorial staff at The New Yorker.

Related Articles

Made in America

Charlie Clifford (Peru 1967–69) is the founder of Tumi Inc., a global travel luggage brand, as well as Roam Luggage.…

Spring/Summer 2025 Issue

This special issue of WorldView makes the definitive case for how Peace Corps makes America stronger, safer, and more prosperous.

Return on Investment

As federal funding for international aid and cultural exchange programs continues to shrink, policymakers are increasingly asking whether these initiatives…

“Bigger Than Peace Corps”

California Service Corps is the largest state-based service program in the U.S. , with more than 10,000 volunteers across the…